- NASA has been keeping tabs on a giant crack in Antarctica’s Brunt Ice Shelf. The crack is rapidly growing, and it’s approaching a second chasm called the “Halloween crack.”

- If the two cracks converge, an iceberg 30 times the size of Manhattan (or twice the size of all of New York City) could break off and float out to sea.

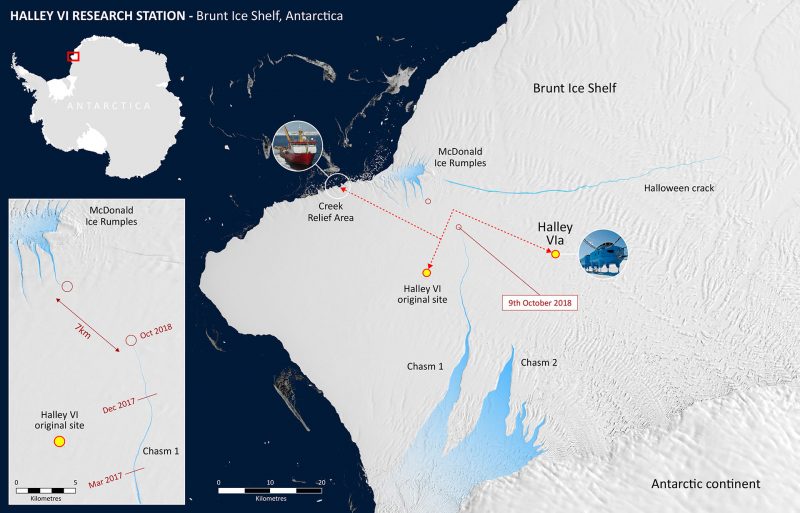

- The region’s shifting ice has forced the nearby British Halley Research Station to relocate and rebuild several times since 1992, most recently in 2017.

A group of NASA scientists is sweating.

Two enormous cracks in Antarctica’s Brunt Ice Shelf – on the continent’s northern rim, some 3,000 miles from the southernmost tip of South America – are accelerating toward each other.

When they meet, they’ll likely release an iceberg into the ocean that’s roughly 30 times the size of Manhattan.

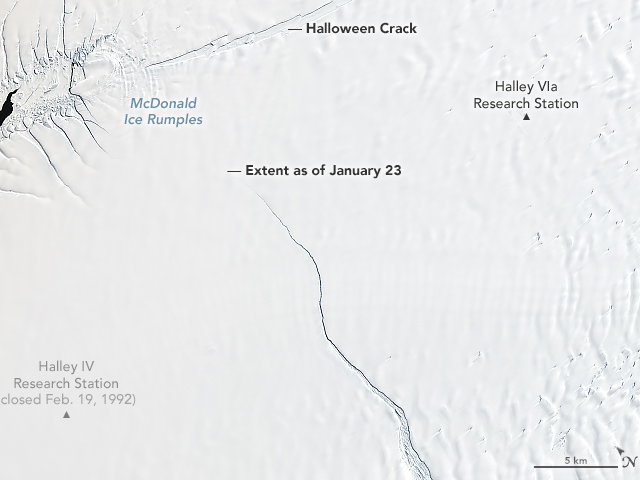

NASA started tracking one of the cracks in October 2016 and aptly named it “Halloween crack.” That chasm is growing eastward from an area called McDonald Ice Rumples – a spot on the ice shelf’s surface where the ice isn’t flat and instead features crevasses and rifts.

But a second crack, which doesn't have its own cool name (it was dubbed "Chasm 1" by the British Antarctic Survey), is more concerning. That crack is southeast of the McDonald Ice Rumples, and it recently started accelerating north, putting it on a collision course with the Halloween crack.

Chasm 1 had been stable for 35 years but started showing signs of movement in 2012. Now it's expanding at a rate of 4 kilometers per year, according to NASA.

The two cracks are only kilometers apart.

When they converge, a piece of ice about 660 square miles in size could break off the ice shelf.

"It's hard to make a projection when it will happen exactly, but it will happen," Stef Lhermitte, an expert who has been closely monitoring Chasm 1's progression, told Earther. Lhermitte thinks that once Chasm 1 expands another 2 1/2 miles, the iceberg could break off. That could occur within "days, but it can also take a year," he said.

NASA has kept tabs on the escalating crack situation using satellite imagery. The slider below juxtaposes an image from January 30, 1986, with another view of the same location on the ice shelf more than 20 years later. While the ice shelf juts farther into the ocean in the 2019 photo, the growth of both Chasm 1 and the Halloween crack is evident.

Giant icebergs could destabilize an entire ice shelf

This isn't the first time Antarctica will lose a giant iceberg, and it won't set any records for size. In 2017, an iceberg the size of Delaware broke off the continent's Larsen C Ice Shelf.

When an iceberg splits off from the continent and starts to melt, it doesn't necessarily contribute to sea-level rise because that ice was already floating on the ocean to begin with. Think of a glass of ice water - as the glass warms, the ice in it melts, but the total volume doesn't increase.

That's the case for this iceberg. But there's a bigger risk: Once this 660-square-mile iceberg gets disconnected from the continent, it could contribute to the destabilization and collapse of the entire Brunt Ice Shelf.

If the whole ice shelf collapses, all the landlocked glaciers that the shelf is keeping in check could melt into the ocean. And that melt could make a significant contribution to sea-level rise.

"The near-term future of Brunt Ice Shelf likely depends on where the existing rifts merge relative to the McDonald Ice Rumples," Joe MacGregor, a glaciologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a press release. "If they merge upstream (south) of the McDonald Ice Rumples, then it's possible that the ice shelf will be destabilized."

A research station may be in jeopardy

It's difficult for scientists to determine how and why certain cracks in the Antarctic ice suddenly begin to grow, but research suggests warming oceans are speeding up Antarctica's melting overall. In the 1980s, Antarctica lost 40 billion tons of ice annually. In the last decade, that number jumped to an average of 252 billion tons per year.

The instability of the region has already impacted British researchers working at the Halley Research Station, where experts study space weather and the planet's changing atmosphere. In 2017, the expanding Chasm 1 forced scientists to prematurely end the winter research season at Halley and close the station early.

Since the station's inception in 1956, there have been six Halleys. The station's current iteration, Halley VIa, moved 14 miles upstream from its original location west of Chasm 1 to the crack's inland side. But the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) decided to leave Halley VIa unmanned in 2018 "for safety reasons" related to the region's "complex and unpredictable glaciological situation."

If the converging cracks destabilize the ice shelf even further, the BAS may have to move their research station again or consider abandoning Halley VIa altogether.

"What we are witnessing is the power and unpredictability of nature," Jane Francis, the director of BAS, said in a press release.